Why we don't prepare enough for things we want

What gets us into trouble is not what we don’t know

It’s what we know for sure that just ain’t so.

Mark Twain 1

In professional kitchens there is a concept I’m fond of: mise en place.

From Wikipedia:

Mise en place (French pronunciation: [mi zɑ̃ ˈplas]) is a French culinary phrase which means “putting in place” or “everything in its place”. It refers to the setup required before cooking, and is often used in professional kitchens to refer to organizing and arranging the ingredients (e.g., cuts of meat, relishes, sauces, par-cooked items, spices, freshly chopped vegetables, and other components) that a cook will require for the menu items that are expected to be prepared during a shift.

Before any meal is served, chefs will prepare not only the ingredients but the meal itself, the number of portions available and organize everything to be ready for customers.

There are a number of interesting life parallels one could take from this seemingly innocuous activity. Personally, and for the context of this essay, I find two things interesting:

Mise en place is tangible: given that you can look at the food that you prepare, it’s visible the amount of preparation required before you start, it’s visible your progress and you can also understand when you are done. You can understand if you’re behind schedule and you can compare yourself to other people. Ingredients are palpable and tangible.

Mise en place is linear: one ingredient contributes to a % of a meal portion. Therefore, each ingredient you prepare contributes linearly to the end meal. The progress you have while preparing the ingredients is therefore easier to understand and plan accordingly[^This is not to say that the mise en place of different meals is the same. But if we plot time and % of completeness of a meal preparation it would be arguably linear].

The reason why I find these two properties interesting is because they are rare and that we assume most other times when we have to plan or prepare for an event are like this.

Imagine a student, preparing for an exam. The preparation for an exam is not tangible. Beyond bullet points and flashcards that you can create (i.e. a pile of information to store in your head), the output of a good preparation is data stored in the student’s hard drive. It’s hard to visualize when you are ready. In fact there are many other factors that make this preparation less obvious and tangible 2

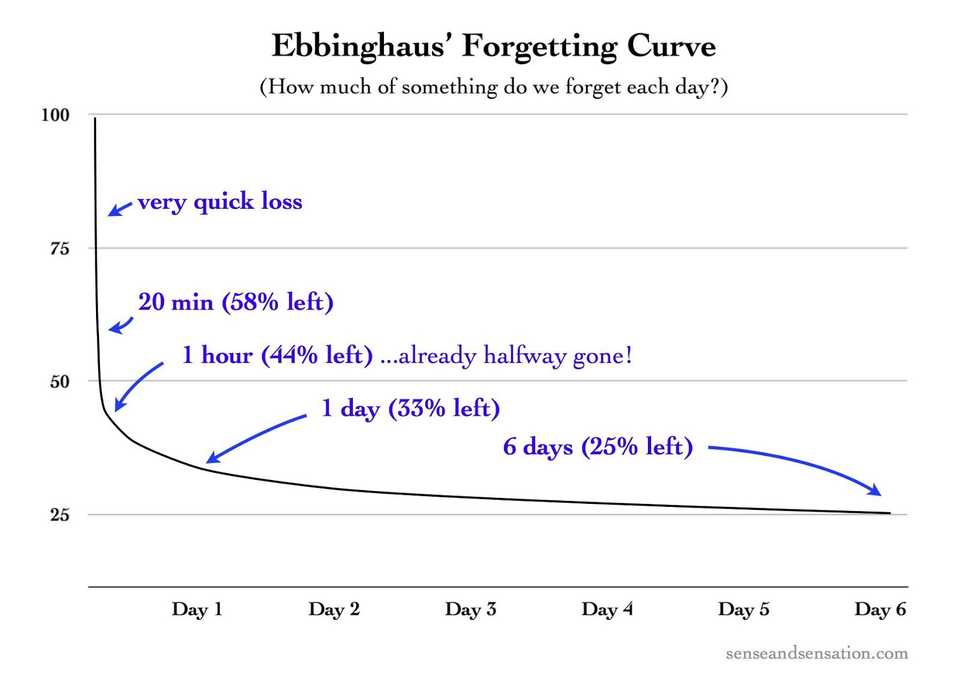

The preparation for an exam is also not linear. In the image above we see the Forgetting Curve which plots how our memory works in recalling information. Studying is essentially trying to counter this. Research shows[^Mace, Cecil Alec. “The psychology of study.” (1932).] that spaced repetition (through exponential memorization of information - recalling information in 1 day, 2 days, 4 days, 8 days, etc). This is why tools like Anki are effective. So, literally, studying and memorization are non-linear.

We have a hard time in moments where these two properties are not present.

Humans are not designed to understand concepts that are not tangible. Take time for example. We approximate our understanding of time to physical space [^How We Make Sense of Time, SA Mind 27, 6, 38-43 (November 2016) - https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-we-make-sense-of-time/]. So you shouldn’t be to hard on yourself if you had a hard time understanding Tenet.

It’s notably hard for humans to understand non linear events[^Fooled by Randomness, Nassim Taleb]. We’re driven to imagine 1-1 relationships between things. Decades of research in cognitive psychology show that the human mind struggles to understand nonlinear relationships. Our brain wants to make simple straight lines[^Linear Thinking in a Nonlinear World, https://hbr.org/2017/05/linear-thinking-in-a-nonlinear-world].

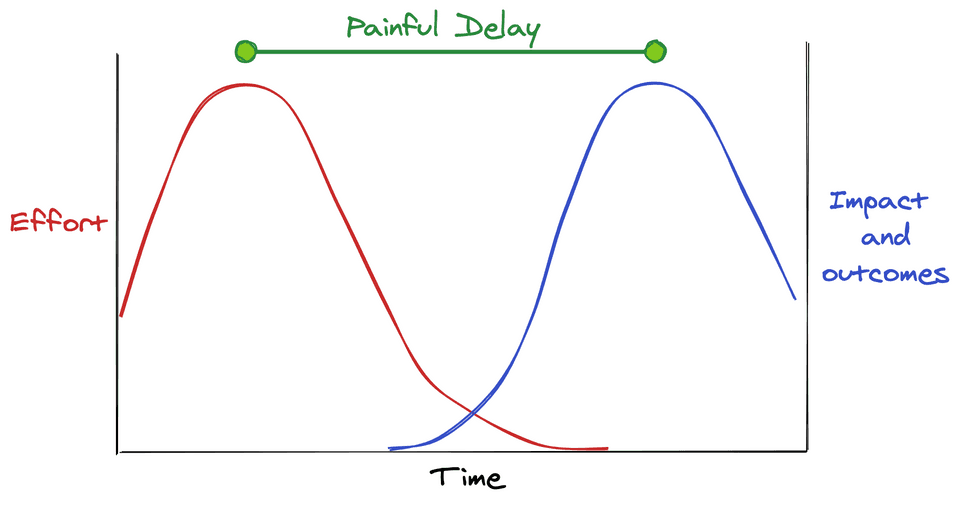

The consequences of not understanding well these two things cause some frustration in our lives. Namely, it widens a gap between our understanding of our efforts and outcomes.

When activities are tangible and linear, it’s easier for humans to understand, predict and plan for this gap. When activities are not tangible and nonlinear, it’s much harder for humans to understand, predict and plan.

Not understanding this gap can cause misjudgment and underestimation. In our example of the student, it easy for the student to overestimate how much she knows. Based on this, the student will not study enough (in this case she won’t prepare herself enough for the test) and have a bad grade.

The student is not alone here. It’s a very human thing to overestimate. Humans are naturally optimistic and sometimes it gets in the way of reason. Humans apply it to circumstances where estimation is required. Humans also have an excessive self-regard tendency. People that have high consideration for themselves are more prone to choosing people like themselves, leading to myopic decisions. This tendency also makes people to consider their own opinions or efforts as better or more important. [^The Psychology of Human Misjudgment, Charlie Munger]

So it’s frustrating not knowing the gap between your efforts and outcomes.

From another perspective, and personally more interesting to me, there is another conclusion: in moments where outcomes are not tangible and nonlinear, it’s not clear to you how much preparation you need to achieve an outcome.

You are probably at this moment doing different tasks, or trying to achieve different goals, and you’re likely not aware of all the preparation required for those. It’s fully clear after the fact, when outcomes arrive. But not while you’re in the process of working. You don’t know when you should start your preparation and for how long. And this is everywhere.

Most specifically, in my own experience, it’s challenging to plan and forecast a business so that outcomes happen when you expect them to happen. Because this relationship (business strategy ⇒ positive outcomes) is not only non linear but highly complex (not tangible), this causes inevitable delays in achieving expectations. Underneath the surface, almost invisible to the naked way, if the right actions are put in place, events are building up to achieve the outcomes you want but, many times, in a timeline different from the one you planned for.

So what can we do about this?

While we’re passengers, we can control our posture. It’s a truism, but it’s probably a good idea to focus on the process and not focus on the outcomes. Just like good decisions don’t depend on the outcome but on the decision making process (or the cost of the alternatives).

You do the best you can in the processes that you control. So prepare early, prepare well. Be paranoid. And leave time for things to work.

When we think too short term, we run the risk of just observing randomness as well as giving up early enough that you don’t get to see the outcomes.

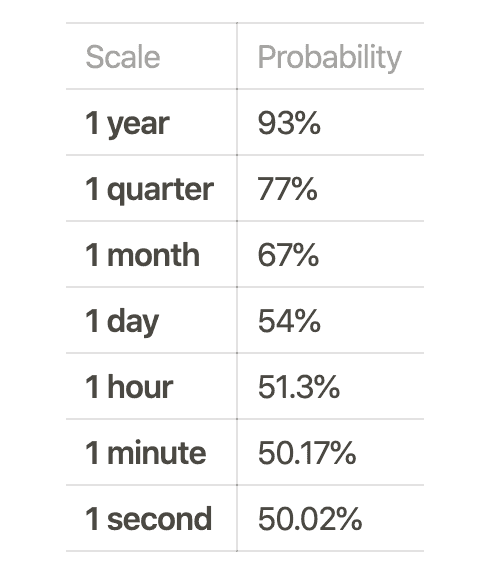

Imagine a scenario: assume an investment with 15% return and 10% margin of error. At the end of the year, there’s 93% probability for an outcome of 15% return. But as we shorten the time frame, the probability will get lower and lower until we get 50% on a second basis[^Fooled by Randomness, Nassim Taleb]. Imagine that you get reports every minute, you get 50% odds on your return. A report every month would mean 67%. If an investor would to overreact based on the hourly report, she would never see any return over time. The point is to put in place long term plans, with short term urgency, and let time do the rest.

Mise en place is everywhere

I’ll answer the question of the title of this post. You don’t prepare yourself enough for things you want because the required preparation is invisible to you. If I had to summarize: preparation is hidden everywhere. We should assume that at any given moment we should be probably preparing for the next outcome we’d like to see happening. Humans are flawed in thinking about the future. Don’t take it personal.

Hey 👋. If you thought this was interesting, tell me about it: @jaimefjorge.

References and notes

- Quote might not be from Mark Twain: https://quoteinvestigator.com/2018/11/18/know-trouble/ ↩

- Pressley, Michael & Yokoi, Linda & Van Meter, Peggy & Etten, Shawn & Freebern, Geoffrey. (1997). Some of the Reasons Why Preparing for Exams Is so Hard: What Can Be Done to Make It Easier?. Educational Psychology Review. 9. 1-38. 10.1023/A:1024796622045. ↩